Memory Management Demystified - Virtual Memory, Page Faults & Performance

Series: Backend Engineering Mastery

Reading Time: 14 minutes

Level: Junior to Senior Engineers

The One Thing to Remember

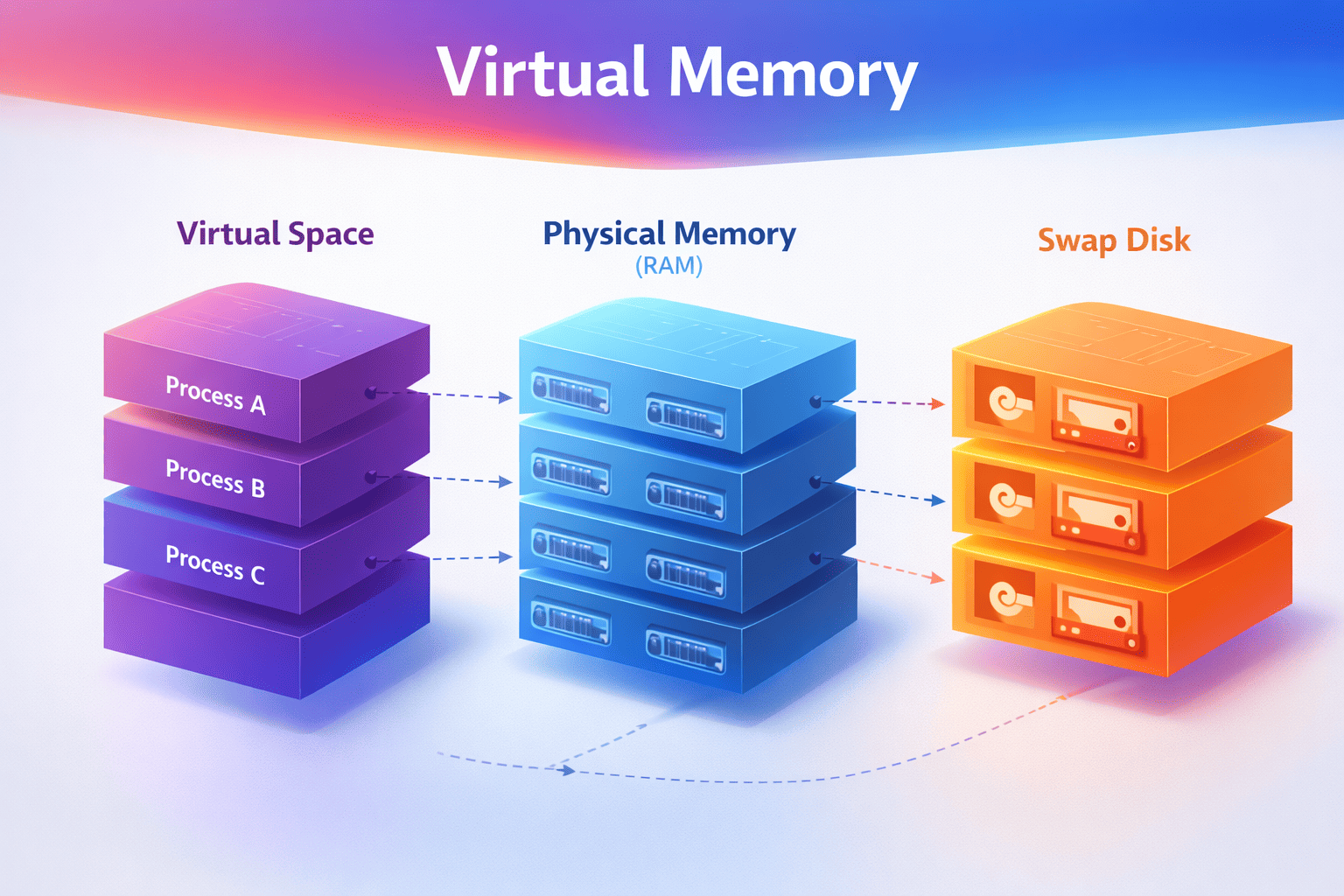

Virtual memory creates the illusion of infinite RAM. Every process thinks it has the entire address space to itself, but the OS juggles physical memory behind the scenes. Understanding this illusion—and when it breaks—is key to writing performant systems.

Building on Article 1

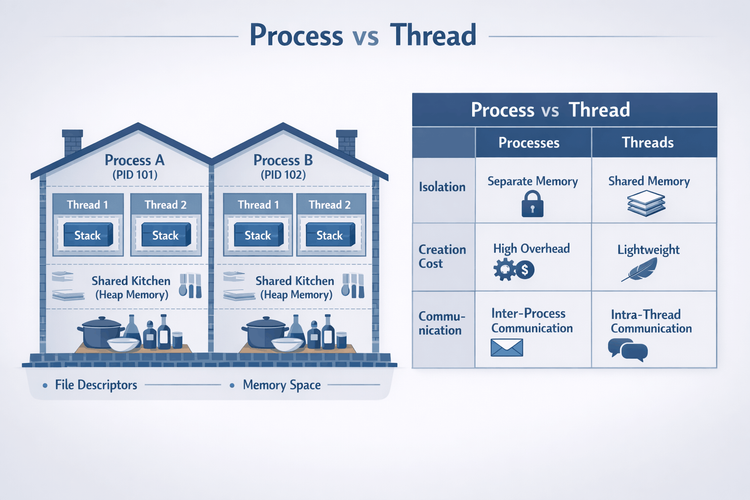

In Article 1: Process vs Thread, you learned that each process gets its own isolated address space—like a house with its own address. But here's the question: How does the OS actually manage all that memory?

Every process thinks it has access to gigabytes of memory, but your server only has so much physical RAM. The OS uses virtual memory to make this work—and when you understand how, you'll finally know why your "2GB process" is only using 100MB of actual RAM.

← Previous: Article 1 - Process vs Thread

Why This Matters

I've seen production systems brought to their knees because engineers didn't understand:

- Why a "2GB memory" process was only using 100MB of actual RAM

- Why adding more RAM didn't fix the performance problem

- Why their container was OOM-killed despite "having memory available"

- Why their Python app suddenly slowed down after running for hours

This isn't academic knowledge—it's the difference between:

-

Debugging memory issues in minutes vs days

- Understanding virtual vs physical memory = you know what to measure

- Not understanding = you throw RAM at the problem, nothing improves

-

Writing efficient code vs accidentally swapping

- Knowing page faults = you avoid touching memory unnecessarily

- Not knowing = your app triggers thousands of page faults, everything slows down

-

Setting correct memory limits

- Understanding RSS vs VmSize = you set limits that actually work

- Not understanding = containers get OOM-killed mysteriously

Memory management knowledge separates engineers who guess from engineers who know.

Quick Win: Check Your Process Memory

Before we dive deeper, let's see what your processes actually use:

# See virtual vs physical memory for a process

cat /proc/$(pgrep python | head -1)/status | grep -E "^(VmSize|VmRSS|VmSwap)"

# VmSize: What the process THINKS it has (virtual)

# VmRSS: What's ACTUALLY in RAM (this matters!)

# VmSwap: What got kicked to disk (should be 0!)

# System-wide memory

free -h

# Look at 'available' - that's what you can actually use

What to look for:

- VmSize >> VmRSS: Process mapped memory but hasn't touched it yet (normal)

- VmSwap > 0: Process is swapping (performance problem!)

- RSS growing over time: Possible memory leak or bloat

The Mental Model

The Hotel Analogy

Think of virtual memory like a hotel:

- Guest (Process): Gets a room number (virtual address) - thinks they have rooms 1-1000

- Front Desk (MMU - Memory Management Unit): Translates room numbers to physical locations

- Room Key (Page Table): The mapping of virtual → physical addresses

- Physical Rooms (RAM): Actual memory - limited supply

- Overflow Parking (Swap): Disk storage when hotel is full - slow but keeps system running

Every guest thinks they have exclusive access to rooms 1-1000, but the hotel dynamically assigns actual rooms based on who's checked in. If the hotel is full, some guests' belongings get moved to overflow parking (swap).

Real example: Your Python process can malloc(1GB) instantly—it just gets a room number. But when it actually tries to use that memory, the OS has to find a physical room (or move someone else's stuff to overflow parking).

Visual Model: Address Translation

VIRTUAL ADDRESS SPACE (per process) PHYSICAL RAM

┌─────────────────────┐ ┌─────────────────────┐

│ │ │ │

│ Stack │ ─────────────────► │ Frame 0x1000 │

│ (grows down) │ │ │

│ │ ├─────────────────────┤

├─────────────────────┤ │ │

│ │ │ Frame 0x1001 │

│ (unmapped - hole) │ NOT MAPPED │ (another process) │

│ │ │ │

├─────────────────────┤ ├─────────────────────┤

│ │ │ │

│ Heap │ ─────────────────► │ Frame 0x1002 │

│ (grows up) │ │ │

│ │ ├─────────────────────┤

├─────────────────────┤ ┌────────► │ │

│ BSS (zero-init) │ ─────────┘ │ Frame 0x1003 │

├─────────────────────┤ │ (shared library) │

│ Data (initialized) │ ─────────────────► │ │

├─────────────────────┤ ├─────────────────────┤

│ Text (code) │ ─────────────────► │ Frame 0x1004 │

└─────────────────────┘ └─────────────────────┘

│

PAGE TABLE │

┌────────┬────────────┬───────┐ │

│ Virtual│ Physical │ Flags │ ▼

│ Page │ Frame │ │ ┌─────────────────────┐

├────────┼────────────┼───────┤ │ │

│ 0x7fff │ 0x1000 │ RW- │ │ DISK (Swap Space) │

│ 0x0040 │ 0x1002 │ RW- │ │ │

│ 0x0001 │ DISK │ --- │ ◄── PAGE │ Swapped out pages │

│ 0x0000 │ 0x1004 │ R-X │ FAULT! │ │

└────────┴────────────┴───────┘ └─────────────────────┘

Key insight: Each process sees its own virtual address space, but the OS

maps these to physical RAM frames (or swap on disk). Multiple processes

can share the same physical frame (like shared libraries).

Quick Jargon Buster

- MMU (Memory Management Unit): Hardware that translates virtual addresses to physical addresses

- Page Table: Data structure mapping virtual pages to physical frames (or disk)

- Page: Fixed-size chunk of virtual memory (usually 4KB)

- Frame: Fixed-size chunk of physical RAM (same size as page)

- Page Fault: When a process accesses a page that's not in RAM

- Swap: Disk space used when RAM is full (slow!)

- RSS (Resident Set Size): Actual physical memory a process is using

- VmSize: Virtual memory size (what process thinks it has)

The Memory Hierarchy: Numbers You Must Know

┌──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ MEMORY HIERARCHY │

├──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ CPU Registers │ < 1ns │ ~KB │ Fastest │

│ ▼ │

│ L1 Cache │ ~1ns │ 32-64KB │ │

│ ▼ │

│ L2 Cache │ ~4ns │ 256KB │ │

│ ▼ │

│ L3 Cache │ ~12ns │ 8-32MB │ │

│ ▼ │

│ RAM │ ~100ns │ 16-512GB │ │

│ ▼ │

│ SSD │ ~16μs │ TB │ │

│ ▼ │

│ HDD │ ~2ms │ TB │ Slowest │

│ │

└──────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

If L1 cache access = 1 second (human scale):

- L2 cache = 4 seconds

- L3 cache = 12 seconds

- RAM = 1.5 minutes

- SSD = 4.4 hours

- HDD = 23 days

A PAGE FAULT (going to disk) is like waiting 23 DAYS vs 1.5 MINUTES!

Why this matters: If your process is swapping (accessing disk), it's 10,000x slower than accessing RAM. This is why understanding memory management is critical for performance.

Page Faults: When the Illusion Breaks

What Happens During a Page Fault

1. Process accesses virtual address 0x12345678

│

▼

2. CPU checks page table → Page not in RAM!

│

▼

3. CPU raises PAGE FAULT exception

│

▼

4. OS page fault handler runs:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ a) Find the page on disk (swap/file) │

│ b) Find free RAM frame (maybe evict) │

│ c) Load page from disk into RAM │

│ d) Update page table │

│ e) Resume the process │

└─────────────────────────────────────────┘

│

▼

5. Process continues, unaware of the ~10ms delay

Types of Page Faults

| Type | Cause | Cost | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minor | Page in memory but not mapped | ~1μs | Lazy allocation, shared libs |

| Major | Page must be loaded from disk | ~10ms | Swapped out page, file read |

Major page faults are 10,000x slower than minor!

Why this matters: If your app triggers major page faults frequently, you'll see random latency spikes. This is why understanding memory access patterns matters.

Trade-offs: Memory Management Decisions

Trade-off #1: Virtual Memory Size vs Physical RAM

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ THE OVERCOMMIT SPECTRUM │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ │

│ Conservative Aggressive │

│ ◄─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────►│

│ │

│ vm.overcommit_memory=2 vm.overcommit_memory=0 │

│ (Never overcommit) (Heuristic overcommit) │

│ │

│ ✓ Never OOM-killed ✓ Run more processes │

│ ✓ Predictable behavior ✓ Memory-efficient │

│ ✗ Wasted memory ✗ OOM killer risk │

│ ✗ malloc() can fail ✗ Unpredictable under pressure │

│ │

│ Use for: Trading systems, Use for: Web servers, │

│ Databases batch jobs │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

What is overcommit? Linux allows processes to allocate more virtual memory than physical RAM exists. This works because most processes don't touch all their allocated memory. But if everyone tries to use it at once, the OOM killer steps in.

Trade-off #2: Swap Space

With Swap:

- ✅ System stays up under memory pressure

- ✅ Rarely-used pages can be evicted

- ❌ Severe performance degradation when swapping

- ❌ "Swap death" - system becomes unresponsive

Without Swap:

- ✅ Predictable performance (no swap thrashing)

- ✅ OOM killer acts quickly

- ❌ Less memory flexibility

- ❌ Sudden death instead of slow death

Recommendation:

- Production servers: Small swap (1-2GB) as emergency buffer

- Containers: Often run without swap (cgroups handle limits)

- Development: Larger swap is fine

- Latency-sensitive apps (AI/ML inference): No swap - you want predictable performance

Trade-off #3: Huge Pages

REGULAR PAGES (4KB): HUGE PAGES (2MB):

─────────────────── ────────────────────

4KB × 1,000,000 pages 2MB × 1,953 pages

= 4GB memory = 4GB memory

Page table: ~2MB Page table: ~4KB

TLB entries needed: many TLB entries needed: few

TLB misses: frequent TLB misses: rare

✓ Fine-grained allocation ✓ Better TLB hit rate

✓ Less internal fragmentation ✓ Less page table memory

✗ Large page tables ✗ Internal fragmentation

✗ More TLB misses ✗ Complex allocation

Use for: General workloads Use for: Databases, JVMs,

large memory apps, AI models

TLB (Translation Lookaside Buffer): CPU cache for page table entries. More TLB misses = slower address translation = slower memory access.

Code Examples

Understanding Memory Allocation

import os

import resource

def show_memory():

"""Show current process memory usage"""

with open('/proc/self/status', 'r') as f:

for line in f:

if line.startswith(('VmSize', 'VmRSS', 'VmSwap', 'VmPeak')):

print(line.strip())

def demonstrate_lazy_allocation():

"""Show that malloc doesn't actually allocate physical memory"""

print("=== Before allocation ===")

show_memory()

# "Allocate" 500MB - this is just virtual address space!

size = 500 * 1024 * 1024 # 500MB

data = bytearray(size) # Virtual memory allocated

print("\n=== After allocation (before touching) ===")

show_memory()

# Notice: VmSize increased, but VmRSS barely changed!

# Now actually touch the memory (trigger page faults)

print("\n=== Touching every page... ===")

for i in range(0, size, 4096): # Touch every 4KB page

data[i] = 1

print("\n=== After touching all pages ===")

show_memory()

# Now VmRSS matches VmSize - physical memory allocated!

demonstrate_lazy_allocation()

Key insight: malloc() or bytearray() returns instantly because it only allocates virtual memory. Physical memory is allocated lazily when you actually touch the pages (page faults).

Monitoring Page Faults

import resource

import mmap

import os

def show_page_faults():

usage = resource.getrusage(resource.RUSAGE_SELF)

print(f"Minor faults (no I/O): {usage.ru_minflt}")

print(f"Major faults (disk I/O): {usage.ru_majflt}")

print("Initial page faults:")

show_page_faults()

# Allocate and touch memory

data = bytearray(100 * 1024 * 1024) # 100MB

for i in range(0, len(data), 4096):

data[i] = 1

print("\nAfter touching 100MB:")

show_page_faults()

# Major faults would indicate swapping - bad for performance!

Memory-Mapped Files (Efficient Large File Access)

import mmap

import os

def read_large_file_traditional(filepath):

"""Traditional: Load entire file into memory"""

with open(filepath, 'rb') as f:

data = f.read() # All in memory at once!

return data[1000000:1000100] # Read 100 bytes

def read_large_file_mmap(filepath):

"""Memory-mapped: OS handles paging automatically"""

with open(filepath, 'rb') as f:

# mmap creates virtual mapping - no immediate memory use

mm = mmap.mmap(f.fileno(), 0, access=mmap.ACCESS_READ)

result = mm[1000000:1000100] # Only this page loaded!

mm.close()

return result

# For a 10GB file:

# Traditional: Needs 10GB RAM

# mmap: Only loads pages you access (~4KB per access)

Use case: Reading large model files, datasets, or logs. Memory-mapped files let the OS page in only what you need.

Real-World Trade-off Stories

Reddit: Memory Bloat vs Memory Leak

Situation: Reddit servers were swapping heavily despite having "enough" RAM.

Investigation:

- VmRSS (resident memory) was high

- No memory leak (Python garbage collector working)

- Problem: Debug list kept references to old request data

Key insight: Memory bloat (holding references you don't need) is more common than true leaks (allocating without freeing).

Fix: Clear debug list after each request. RSS dropped 40%.

Lesson: Check what's keeping objects alive, not just what's allocated.

Trading Firm: GC + Swap = Disaster

Situation: Java trading system had random 100ms+ latency spikes.

Investigation:

- GC was running frequently

- Some GC cycles took much longer than others

- Correlation: Long GCs when accessing cold heap pages

Root cause:

- JVM heap was 32GB

- System had 64GB RAM, but also ran other processes

- Cold heap pages were swapped out

- GC touched all pages → Major page faults → 100ms+ delays

Fix:

# Lock JVM heap in physical memory

java -XX:+AlwaysPreTouch -XX:+UseLargePages ...

# Or use mlockall()

Lesson: GC + Swap is a deadly combination. Lock critical memory.

Elasticsearch: JVM Heap Size Sweet Spot

Trade-off: Larger heap = more cache = better performance... right?

Reality:

- Heap > 32GB loses compressed object pointers (CompressedOops)

- Effectively: 32GB heap can address MORE objects than 40GB heap

- GC pauses increase with heap size

Recommendation:

- Never exceed 50% of RAM for JVM heap

- Stay under 32GB to keep CompressedOops

- Leave room for OS page cache

Good: 64GB RAM → 30GB heap, 34GB for OS cache

Bad: 64GB RAM → 60GB heap, 4GB for OS cache

AI Model Serving: Memory Locking for Predictable Latency

Situation: ML inference service had unpredictable latency—sometimes 10ms, sometimes 100ms+.

Investigation:

- Model weights loaded into memory

- Some inference requests were fast, others slow

- Correlation: Slow requests when model pages were swapped out

Root cause:

- Model was 8GB, system had 16GB RAM

- Other processes caused memory pressure

- OS swapped out cold model pages

- Inference touched swapped pages → major page faults → 100ms+ latency

Fix:

# Lock model in physical memory (mlock)

import ctypes

libc = ctypes.CDLL("libc.so.6")

# After loading model

model_data = load_model() # 8GB

libc.mlock(model_data, len(model_data)) # Lock in RAM

Alternative: Use huge pages for model memory:

# Allocate huge pages

echo 4096 > /proc/sys/vm/nr_hugepages

# Use in application

# (depends on your ML framework)

Trade-off accepted:

- Less flexibility (can't swap model out)

- But: Predictable latency (no page faults during inference)

Lesson: For latency-sensitive AI workloads, lock critical memory. Predictable 10ms is better than unpredictable 10-100ms.

Common Confusions (Cleared Up)

"Virtual memory is the same as swap!"

Reality: Virtual memory is the abstraction (every process gets its own address space). Swap is disk storage used when RAM is full. They're related but different:

- Virtual memory: Always exists (even without swap)

- Swap: Optional disk space for when RAM is full

"More virtual memory = more performance!"

Reality: Virtual memory is just an address space. What matters is:

- RSS (Resident Set Size): How much is actually in RAM

- Page faults: How often you're going to disk

A process with 10GB virtual memory but 100MB RSS is fine. A process with 2GB virtual memory but 1.5GB RSS might be swapping.

"malloc() allocates physical memory immediately!"

Reality: malloc() only allocates virtual memory. Physical memory is allocated lazily when you touch the pages (lazy allocation). This is why malloc(1GB) returns instantly but accessing it can be slow.

"If I have swap, I can't run out of memory!"

Reality: Swap prevents OOM-kills but causes severe performance degradation. If you're actively swapping, your system is effectively broken. Better to OOM-kill one process than have everything slow to a crawl.

Debugging Memory Issues

The Three Numbers You Must Know

# Check these for any process

cat /proc/<PID>/status | grep -E "^(VmSize|VmRSS|VmSwap)"

VmSize: Total virtual memory (what process thinks it has)

VmRSS: Resident Set Size (what's actually in RAM)

VmSwap: How much is swapped out (should be ~0 in production)

# If VmSwap > 0, you have a problem!

System-Wide Memory Check

# Quick overview

free -h

total used free shared buff/cache available

Mem: 62Gi 24Gi 1.2Gi 1.0Gi 36Gi 35Gi

Swap: 2.0Gi 500Mi 1.5Gi

# What matters:

# - 'available' = how much can be used (including reclaimable cache)

# - 'buff/cache' = disk cache (good! can be reclaimed)

# - Swap used > 0 = investigate!

Finding Memory Hogs

# Top memory consumers

ps aux --sort=-%mem | head -10

# Memory usage by process name

ps -eo pid,comm,rss --sort=-rss | head -20

# Detailed process memory map

pmap -x <PID> | tail -20

# Watch for swapping in real-time

vmstat 1

# Look at 'si' (swap in) and 'so' (swap out) columns

# Non-zero = active swapping = performance problem

Common Mistakes

Mistake #1: "My process uses 2GB" (Looking at VmSize)

Why it's wrong: Virtual memory ≠ physical memory.

VmSize: 2048000 kB ← This is what people often quote

VmRSS: 150000 kB ← This is actual physical memory used!

A process can map 2GB but only touch 150MB.

Right approach: Look at RSS (Resident Set Size) for actual usage.

Mistake #2: "Adding more RAM will help"

Why it's wrong: If your working set fits in RAM, more RAM won't help.

Diagnostic:

# Check major page faults

cat /proc/<PID>/stat | awk '{print $12}' # majflt field

# If near zero, RAM isn't your bottleneck!

Right approach: Profile first. More RAM only helps if you're actually memory-constrained.

Mistake #3: "Memory leaks cause OOM"

Why it's wrong: Most "leaks" are actually memory bloat - keeping references you don't need.

Right approach:

- Use heap profilers (py-spy for Python, async-profiler for Java)

- Look at what's keeping objects alive

- Check for growing collections (caches without eviction)

Decision Framework: Memory Configuration

□ What's the working set size of my application?

→ Measure RSS under normal load

→ Ensure RAM > working set + OS needs

□ Should I use swap?

→ Production servers: Small swap (1-2GB) as safety net

→ Latency-sensitive: Consider no swap

→ Development: Larger swap is fine

□ Should I use huge pages?

→ Heap > 8GB and long-running: Yes

→ Many small processes: No

→ Databases (PostgreSQL, MySQL): Usually yes

→ AI/ML models: Often yes (better TLB hit rate)

□ How should I set memory limits (containers/cgroups)?

→ limit = expected RSS + 20% headroom

→ Don't set limit = total RAM (leave room for OS)

□ What memory overcommit policy?

→ Mission-critical: Conservative (overcommit_memory=2)

→ General servers: Default heuristic (overcommit_memory=0)

Memory Trick

"VRSS" - What to check:

- Virtual: What the process thinks it has (VmSize)

- Resident: What's actually in RAM (RSS - this matters!)

- Shared: Memory shared with other processes

- Swap: What got kicked to disk (bad if high)

Self-Assessment

Before moving on, make sure you can:

- [ ] Explain why

malloc(1GB)returns instantly but accessing it is slow - [ ] Identify the difference between minor and major page faults

- [ ] Diagnose memory pressure from

free -houtput - [ ] Explain when huge pages help and when they don't

- [ ] Know why GC + swap is a dangerous combination

- [ ] Explain the difference between VmSize and RSS

- [ ] Know when to lock memory for latency-sensitive workloads (like AI inference)

Key Takeaways

- Virtual ≠ Physical: VmSize is not your actual memory usage; RSS is

- Page faults matter: Major faults (disk access) are 10,000x slower

- Measure before optimizing: More RAM only helps if you're actually constrained

- Swap is a trade-off: Prevents OOM but causes severe slowdowns

- Memory bloat ≠ Memory leak: Most issues are from keeping references, not forgetting to free

- Lock critical memory: For latency-sensitive apps (AI/ML), lock model weights in RAM

What's Next

Now that you understand how memory works, the next question is: How does data actually get written to disk?

In the next article, Article 3: File I/O & Durability - Why fsync() Is Your Best Friend (And Worst Enemy), you'll learn:

- Why your data might be lost even after

write()returns - How the OS buffers writes for performance

- When to use

fsync()and when to avoid it - The trade-offs between durability and performance

This connects directly to memory management—data flows from your process's memory, through the OS page cache, to disk. Understanding this path is critical for building durable systems.

→ Continue to Article 3: File I/O & Durability

This article is part of the Backend Engineering Mastery series. Each article builds on the previous—you learned about process isolation in Article 1, and now you understand how memory works within those processes.